La Apis melífera o abeja melífera es un conocido insecto productor y almacenador de miel, y a nivel agrícola es altamente esencial en la polinización de 13 cultivos e importante en la polinización de al menos otros 57 [1]. Es por esto que en ciertas ocasiones se manifiesta preocupación a nivel social y en los medios de comunicación por una eventual reducción global en el número de colmenas, y generalmente suele culparse a los cultivos genéticamente modificados (GM), o transgénicos, y sus fitosanitarios asociados. ¿Qué hay de verdad y mito en todo esto?

Si revisamos datos históricos, se han reportado grandes mortandades de abejas en los años 950, 992 y 1443 en Irlanda [2], así como diferentes desapariciones masivas sin causas claras desde fines del siglo XIX. Diversas desapariciones ocurrieron desde 1906 hasta la década de 1960 en Estados Unidos, Australia y Canadá [3], y desde la década de 1970 hasta 2006 se observaron reducciones en la cantidad global de colmenas de abejas, especialmente en el hemisferio norte [4]. Se habían acuñado distintos nombres para referirse a estas múltiples desapariciones, pero en 2006 se renombró el fenómeno como “Síndrome de Colapso de Colonias” (CCD, por su sigla en inglés).

Los mecanismos causantes del CCD son desconocidos pero se han propuesto diversas causas, que podrían ser sinérgicas en conjunto. Entre ellas se encuentran el letal ácaro varroa y los virus que porta, como el virus de parálisis aguda de Israel y el virus de las alas deformes; parásitos (especialmente Nosepa apis); hongos; inmunodeficiencias; factores genéticos; antibióticos y pesticidas; desnutrición; métodos de cruce; baja variabilidad poblacional; el estrés de la apicultura migratoria o trashumante; pérdida de hábitats, entre otros [5][6].

Se debe tomar en cuenta que este no es un fenómeno reciente, y los cultivos GM recién se cultivan a gran escala desde 1996, y además, el CCD también se ha reportado en países que no siembran cultivos GM, por ejemplo, en el Reino Unido, Bélgica, Francia, Países Bajos, Grecia, Italia, Suiza y Alemania [7].

Entonces ¿Por qué se culpa a los cultivos GM? ¿Cómo se puede saber si efectivamente pueden o no ejercer algún tipo de impacto negativo en las abejas? Para responder esto, se debe que analizar los dos tipos principales de cultivos GM a nivel comercial: resistentes a insectos y tolerantes a herbicidas.

En el caso de los cultivos GM resistentes a insectos, estos han sido modificados para expresar una (o algunas) de las más de 200 tipos de proteína Bt, la cual es producida en la naturaleza por la bacteria Bacillus thuringiensis, una bacteria natural del suelo. Por su especificidad permite ser usada como insecticida exclusivo para insectos plaga del orden Lepidóptera sin afectar a otros insectos no plaga, como la abeja (que pertenece al orden Hymenoptera), mariposas, chinitas, entre otros.

[Recomendado: Los cultivos transgénicos son seguros para las mariposas monarca]

La proteína Bt tiene un extenso historial de seguridad ya que se ha aplicado en forma de spray en agricultura convencional y orgánica desde la década de 1920 [8][9], e incluso es mucho más segura para las abejas que otros insecticidas y fungicidas naturales usados en agricultura orgánica [10]. En la bibliografía académica hay 36 estudios científicos revisados por pares que avalan la inocuidad de los cultivos Bt para las abejas (ver Anexo: Tabla N°1).

Para el segundo caso, cultivos GM tolerantes a herbicidas, estos han sido modificados para tolerar un herbicida específico, principalmente glifosato, lo cual permite realizar un mejor control de malezas y adoptar prácticas ambientalmente amigables como la siembra directa. Cabe mencionar que el glifosato actúa inhibiendo la enzima EPSPS que participa exclusivamente en el metabolismo de plantas. Esta enzima no existe fuera del reino vegetal, por lo cual no afecta el metabolismo de las abejas u otras especies del reino animal.

Este herbicida también cuenta con un historial de uso seguro y baja toxicidad (ambiental, humana y animal) desde 1974 en agricultura convencional, y desde 1996 en cultivos GM [11][12]. Se ha estudiado ampliamente su aplicación en laboratorio y en campo para evaluar su potencial toxicidad para las abejas, sin encontrar efectos dañinos tanto para individuos adultos y sus larvas. Diversos estudios revisados por pares así como informes de agencias regulatorias y universidades avalan su inocuidad para estos insectos polinizadores (ver Anexo: Tabla N°2).

La siembra de cultivos Bt ha permitido reducir enormemente la aplicación de pesticidas, y la adopción de cultivos tolerantes a glifosato ha reducido el uso de fitosanitarios de mayor toxicidad. Ambos factores han permitido una mayor sustentabilidad ambiental y una reducción del impacto a la biodiversidad, incluyendo insectos no plaga como las abejas [13][14].

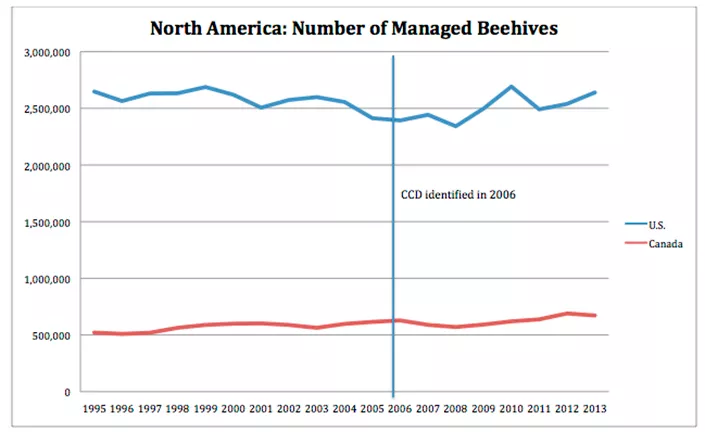

Finalmente, retomando el problema del CCD, si se observa el nivel de colmenas administradas en Estados Unidos y Canadá [Imagen 1], primer y quinto mayor productor mundial de cultivos transgénicos respectivamente, estas han aumentado desde 521.000 en 1995 a un récord de 672.000 en 2013 en Canadá, y en el caso de Estados Unidos, se han mantenido estables a lo largo de las dos últimas décadas [15][16]; incluso estudios de Departamento de Agricultura de Estados Unidos han arrojado que el número de colmenas ha aumentado en el último tiempo, y que durante 2016 el número de colmenas perdidas por el CCD fue de un 27% menos a los datos registrado un año antes [17].

Fuente: USDA y Statistics Canada

Sin duda se debe avanzar en desarrollar estrategias efectivas para detectar con precisión las causantes del CCD, pero eso no debe implicar que de manera infundada o basada en el temor y desconocimiento se obstaculicen tecnologías como los cultivos transgénicos, que han demostrado ampliamente su inocuidad.

| Referencias: |

| 1.- Klein A-M, Vaissiere BE, Cane JH, Steffan-Dewenter I, Cunningham SA, Kremen C, Tscharntke T. (2007). Importance of pollinators in changing landscapes for world crops. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B. Biol. Sci. 274: 303–313 |

| 2.- Oldroyd BP (2007) What’s Killing American Honey Bees? PLoS Biol 5(6): e168. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0050168 |

| 3.- Robyn M. Underwood and Dennis van Engelsdorp.”Colony Collapse Disorder: Have We Seen This Before?”. The Pennsylvania State University, Department of Entomology. Retrieved: November 29, 2010. |

| 4.- Watanabe, M. (1994). “Pollination worries rise as honey bees decline”. Science 265 (5176): 1170. DOI:10.1126/science.265.5176.1170 |

| 5.- Becher, M. A., Osborne, J. L., Thorbek, P., Kennedy, P. J., & Grimm, V. (2013). Towards a systems approach for understanding honeybee decline: a stocktaking and synthesis of existing models. The Journal of Applied Ecology,50(4), 868–880. http://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2664.12112 |

| 6.- USDA (October 17, 2012). Report on the National Stakeholders Conference on Honey Bee Health: National Honey Bee Health Stakeholder Conference Steering Committee (Report). Retrieved: November 29, 2015. Available at: http://www.usda.gov/documents/ReportHoneyBeeHealth.pdf |

| 7.- EFSA (July 4, 2013). Bee health. Retrieved: November 29, 2015. Retrieved: November, 29, 2015. Available at: http://www.efsa.europa.eu/en/topics/topic/beehealth |

| 8.- Wei, Jun-Zhi; Hale, Kristina; Carta, Lynn; Platzer, Edward; Wong, Cynthie; Fang, Su-Chiung; Aroian, Raffi V. (2003). “Bacillus thuringiensis crystal proteins that target nematodes”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 100 (5): 2760–5. doi:10.1073/pnas.0538072100. |

| 9.- Lemaux, Peggy G. (2008). “Genetically Engineered Plants and Foods: A Scientist’s Analysis of the Issues (Part I)”. Annual Review of Plant Biology 59: 771–812.doi:10.1146/annurev.arplant.58.032806.103840 |

| 10.- Mader, E. (2015). “Organic Farming for Bees: Conservation of Native Crop Pollinators in Organic Farming Systems” – Organic-Approved Pesticides. Minimizing Risk to Pollinators. [online] Portland, OR: The Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation, pp.2-5. Available at: https://www.organicconsumers.org/sites/default/files/organic_farming_for_bees.pdf [Accessed 29 Nov. 2015]. |

| 11.- EPA (September, 1993). Registration Decision Fact Sheet for Glyphosate (EPA-738-F-93-011). R.E.D. FACTS. Retrieved: November 29, 2015. Available at: http://www3.epa.gov/pesticides/chem_search/reg_actions/reregistration/red_PC-417300_1-Sep-93.pdf |

| 12.- EFSA (European Food Safety Authority), 2015. Conclusion on the peer review of the pesticide risk assessment of the active substance glyphosate. EFSA Journal 2015;13(11):4302, 107 pp. doi:10.2903/j.efsa.2015.4302 |

| 13.- Graham Brookes & Peter Barfoot (2015) Global income and production impacts of using GM crop technology 1996–2013, GM Crops & Food, 6:1, 13-46, DOI: 10.1080/21645698.2015.1022310 |

| 14.- Klümper W, Qaim M (2014) A Meta-Analysis of the Impacts of Genetically Modified Crops. PLoS ONE 9(11): e111629. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0111629 |

| 15.- Statistics Canada. Table 001-0007 – Production and value of honey, annual (number unless otherwise noted), CANSIM (database). Accessed: November 29, 2015. Disponible en: http://www5.statcan.gc.ca/cansim/a26?lang=eng&retrLang=eng&id=0010007&paSer=&pattern=&stByVal=1&p1=1&p2=31&tabMode=dataTable&csid= |

| 16.- USDA. Honey – National Agricultural Statistics Service. Consultado: 29 de Noviembre, 2015. Disponible en: http://usda.mannlib.cornell.edu/MannUsda/viewDocumentInfo.do?documentID=1191 |

| 17.- USDA. Honey Bee Colonies. Agosto, 2017. Disponible en: https://www.usda.gov/nass/PUBS/TODAYRPT/hcny0817.pdf |

Anexo

| TABLA N°1- Estudios publicados en revistas científicas (revisadas por pares) que avalan la inocuidad de los cultivos transgénicos Bt para las abejas. |

| 1. Arpaia S. 1996. Ecological impact of Bt-transgenic plants: 1. Assessing posible effects of CryIIIB toxin on honey bee (Apis mellifera L.) colonies. J Genet Breed 50:315-19 |

| 2. Babendreier D, Kalberer NM, Romeis J, Fluri P, Mulligan E and Bigler F. 2005. Influence of Bt-transgenic pollen, Bt-toxin and protease inhibitor (SBTI) ingestion on development of the hypopharyngeal glands in honeybees. Apidologie 36:585-94 |

| 3. Babendreier D, Joller D, Romeis J, Bigler F, Widmer F. 2007. Bacterial community structures in honeybee intestines and their response to two insecticidal proteins. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 59(3):600-10 |

| 4. Dai PL, Zhou W, Zhang J, Jiang WY, Wang Q, Cui HJ, Sun JH, Wu YY, Zhou T. 2012. The effects of Bt Cry1Ah toxin on worker honeybees (Apis mellifera ligustica and Apis cerana cerana). Apidologie 43:384-91 |

| 5. Dai PL, Zhou W, Zhang J, Cui HJ, Wang Q, Jiang WY, Sun JH, Wu YY, Zhou T. 2012. Field assessment of Bt cry1Ah corn pollen on the survival, development and behavior of Apis mellifera ligustica. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 79:232-7 |

| 6. Dai PL, Zhou W, Zhang J, et al. 2015. Effects of Bt cry1Ah corn pollen on immature worker survival and development of Apis cerana cerana. J Apicultural Res. 54(1) doi: 10.1080/00218839.2015.1035075 |

| 7. Duan JJ, Marvier M, Huesing J, Dively G, Huang ZY. 2008. A Meta-Analysis of Effects of Bt Crops on Honey Bees (Hymenoptera: Apidae). PlosOne 3(1):e1415. |

| 8. Geng LL, Cui HJ, Dai PL, Lang ZH, Shu CL, Zhou T, Song FP, Zhang J. 2013. The influence of Bt-transgenic maize pollen on the bacterial diversity in the midgut of Apis mellifera ligústica. Apidologie 44:198-208 |

| 9. Grabowski M, Dabrowski ZT. 2012. Evaluation of the impact of the toxic protein Cry1Ab expressed by the genetically modified cultivar MON810 on honey bee (Apis mellifera L.) behavior. Med. Weter. 68(10):630-3 |

| 10. Han P, Niu CY, Lei CL, Cui JJ, Desneux N. 2010. Use of an innovative T-tube maze assay and the proboscis extension response assay to assess sublethal effects of GM products and pesticides on learning capacity of the honey bee Apis mellifera L. Ecotoxicology 19(8):1612-9 |

| 11. Han P, Niu CY, Biondi A, Desneux N. 2012. Does transgenic Cry1Ac + CpTI cotton pollen affect hypopharyngeal gland development and midgut proteolytic enzyme activity in the honey bee Apis mellifera L. (Hymenoptera, Apidae)? Ecotoxicology 21(8):2214-21 |

| 12. Hanley AV, Huang ZY, Pett WL. 2003. Effects of dietary transgenic Bt corn pollen on larvae of Apis mellifera and Galleria mellonella. J Apic Res 42:77-81 |

| 13. Hendriksma HP, Härtel S, Steffan-Dewenter I. 2011. Testing pollen of single and stacked insect-resistant Bt-maize on in vitro reared honey bee larvae. PlosOne 6(12):e28174 |

| 14. Hendriksma HP, Härtel S, Babendreier D, von der Ohe W, Steffan-Dewenter I. 2012. Effects of multiple Bt proteins and GNA lectin on in vitro-reared honey bee larvae. Apidologie 43:549-60 |

| 15. Hendriksma HP, Küting M, Härtel S, Näther A, Dohrmann AB, Steffan-Dewenter I, Tebbe CC. 2013. Effect of stacked insecticidal Cry proteins from maize pollen on nurse bees (Apis mellifera carnica) and their gut bacteria. PlosOne 8(3):e59589 |

| 16. Huang ZY, Hanley AV, Pett WL, Langenberger M, Duan JJ. 2004. Field and semifield evaluation of impacts of transgenic canola pollen on survival and development of worker honey bees. J Econ Entomol. 97(5):1517-23 |

| 17. Lehrman A. 2007. Does pea lectin expressed transgenically in oilseed rape (Brassica napus) influence honey bee (Apis mellifera) larvae? Environ Biosafety Res.6(4):271-8 |

| 18. Lima M, Pires C, Guedes R, Nakasu E, Lara M, Fontes E, Sujii E, Dias S, Campos L. 2011. Does Cry1Ac Bt-toxin impair development of worker larvae of Africanized honey bee? J. Appl. Entomol. 135(6): 415-22 |

| 19. Lima M, Pires C, Guedes R, Campos L. 2013. Lack of lethal and sublethal effects of Cry1Ac Bt-toxin on larvae of the stingless bee Trigona spinipes. Apidologie 44:21-28 |

| 20. Liu B, Xu C, Yan F, Gong R. 2005. The impacts of the pollen of insect-resistant transgenic cotton on honey bees. Biodiversity Conserv 14:3487-96 |

| 21. Liu B, Shu C, Xue K, Zhou K, Li X, Liu D, Zheng Y, Xu C. 2009. The oral toxicity of the transgenic Bt+CpTI cotton pollen to honeybees (Apis mellifera). Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 72(4):1163-9 |

| 22. Malone LA, Burgess EPJ, Stefanovic D. 1999. Effects of a Bacillus thuringiensis toxin, two Bacillus thuringiensis biopesticide formulations, and a soybean trypsin inhibitor on honey bee (Apis mellifera L.) survival and food consumption. Apidologie 30:465-73 |

| 23. Malone LA, Burgess EPJ, Gatehouse HS, Voisey CR, Tregidga EL, et al. 2001. Effects of ingestion of a Bacillus thuringiensis toxin and a trypsin inhibitor on honey bee flight activity and longevity. Apidologie 32:57-68 |

| 24. Malone LA, Pham-Delegue MH. 2001. Effects of transgene products on honey bees (Apis mellifera) and bumblebees (Bombus sp.). Apidologie 32:287-304 |

| 25. Malone LA, Todd JH, Burgess EPJ, Christeller JT. 2004. Development of hypopharyngeal glands in adult honey bees fed with a Bt toxin, a biotin-binding protein and a protease inhibitor. Apidologie 35:655-64 |

| 26. Niu L, Ma Y, Mannakkara A, Zhao Y, Ma W, Lei C, Chen L. 2013. Impact of single and stacked insect-resistant Bt-cotton on the honey bee and silkworm. PlosOne 8(9):e72988 |

| 27. Niu L, Ma W, Lei Ch, Jurat-Fuentes JL, Chen L. 2017. Herbicide and insect resistant Bt cotton pollen assessment finds no detrimental effects on adult honey bees. Environmental Pollution, 230:479-485 |

| 28. Ping-Li Dai, Wei Zhou, Jie Zhang, Zhi-Hong Lang, Ting Zhou, Qiang Wang, Hong-Juan Cui, Wei-Yu Jiang & Yan-Yan Wu (2015) Effects of Bt cry1Ah corn pollen on immature worker survival and development of Apis cerana cerana, Journal of Apicultural Research, 54:1, 72-76, DOI: 10.1080/00218839.2015.1035075 |

| 29. Ping-Li Dai, Hui-Ru Jia, Li-Li Geng, Qing-Yun Diao. (2016). Bt Toxin Cry1Ie Causes No Negative Effects on Survival, Pollen Consumption, or Olfactory Learning in Worker Honey Bees (Hymenoptera: Apidae). Journal of Economic Entomology, 1-6. |

| 30. Ramirez-Romero R, Desneux N, Decourtye A, Chaffiol A, Pham-Delègue MH. 2008. Does Cry1Ab protein affect learning performances of the honey bee Apis mellifera L. (Hymenoptera, Apidae)? Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 70(2):327-33 |

| 31. Rose R, Dively GP, Pettis J. 2007. Effects of Bt corn pollen on honey bees: Emphasis on protocol development. Apidologie 38:368-77 |

| 32. Sims SR. 1995. Bacillus thuringiensis var. kurstaki [Cry1A(c)] protein expressed in transgenic cotton: Effects on beneficial and other non-target insects. Southwest Entomol. 20: 493-500 |

| 33. Sims SR. 1997. Host activity spectrum of the CryIIA Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. kurstaki protein: Effects on lepidoptera, diptera, and non-target arthropods. Southwest Entomol. 22:395-404 |

| 34. Tan J, Levine SL, Bachman PM, Jensen PD, Mueller GM, Uffman JP, Meng C, Song Z, Richards KB, Beevers MH. (2015). No impact of DvSnf7 RNA on honey bee (Apis mellifera L.) adults and larvae in dietary feeding tests. Environ Toxicol Chem. doi: 10.1002/etc.3075 |

| 35. Wang YY, Li YH, Huang ZY, Chen XP, Romeis J, Dai PL, Peng YF. (2015). Toxicological, Biochemical, and Histopathological Analyses Demonstrating That Cry1C and Cry2A Are Not Toxic to Larvae of the Honeybee, Apis mellifera. J Agric Food Chem. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.5b01662 |

| 36. Wang Y, Dai P, Chen X, Romeis J, Shi J, Peng Y, Li Y. (2016). Ingestion of Bt rice pollen does not reduce the survival or hypopharyngeal gland development ofApis mellifera adults. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry; DOI: 10.1002/etc.3647 |